he clockwise warm-water

North Atlantic Gyre occupies the northern Atlantic, and the counter-clockwise warm-water

South Atlantic Gyre appears in the southern Atlantic.

[5]

In the North Atlantic surface circulation is dominated by three inter-connected currents: the

Gulf Stream which flows north-east from the North American coast at

Cape Hatteras; the

North Atlantic Current, a branch of the Gulf Stream which flows northward from the

Grand Banks; and the

Subpolar Front,

an extension of the North Atlantic Current, a wide, vaguely defined

region separating the subtropical gyre from the subpolar gyre. This

system of currents transport warm water into the North Atlantic, without

which temperatures in the North Atlantic and Europe would plunge

dramatically.

[33]

In the subpolar gyre of the North Atlantic warm subtropical waters are

transformed into colder subpolar and polar waters. In the Labrador Sea

this water flows back to the subtropical gyre.

North of the North Atlantic Gyre, the cyclonic

North Atlantic Subpolar Gyre

plays a key role in climate variability. It is governed by ocean

currents from marginal seas and regional topography, rather than being

steered by wind, both in the deep ocean and at sea level.

[34] The subpolar gyre forms an important part of the global

thermohaline circulation. Its eastern portion includes

eddying branches of the

North Atlantic Current

which transport warm, saline waters from the subtropics to the

north-eastern Atlantic. There this water is cooled during winter and

forms return currents that merge along the eastern continental slope of

Greenland where they form an intense (40–50

Sv) current which flows around the continental margins of the

Labrador Sea. A third of this water become parts of the deep portion of the

North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW). The NADW, in its turn, feed the

meridional overturning circulation

(MOC), the northward heat transport of which is threatened by

anthropogenic climate change. Large variations in the subpolar gyre on a

decade-century scale, associated with the

North Atlantic Oscillation, are especially pronounced in

Labrador Sea Water, the upper layers of the MOC.

[35]

The South Atlantic is dominated by the anti-cyclonic southern subtropical gyre. The

South Atlantic Central Water originates in this gyre, while

Antarctic Intermediate Water originates in the upper layers of the circumpolar region, near the

Drake Passage

and Falkland Islands. Both these currents receive some contribution

from the Indian Ocean. On the African east coast the small cyclonic

Angola Gyre lies embedded in the large subtropical gyre.

[36] The southern subtropical gyre is partly masked by a wind-induced

Ekman layer. The residence time of the gyre is 4.4–8.5 years.

North Atlantic Deep Water flows southerward below the

thermocline of the subtropical gyre.

[37]

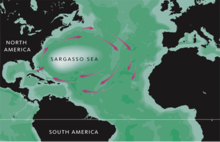

Sargasso Sea

Approximate extent of the Sargasso Sea

The Sargasso Sea in the western North Atlantic can be defined as the area where two species of

Sargassum (

S. fluitans and

natans) float, an area 4,000 km (2,500 mi) wide and encircled by the

Gulf Stream,

North Atlantic Drift, and

North Equatorial Current. This population of seaweed probably originated from Tertiary ancestors on the European shores of the former

Tethys Ocean and has, if so, maintained itself by

vegetative growth, floating in the ocean for millions of years.

[38]

Sargassum fish (Histrio histrio)

Other species endemic to the Sargasso Sea include the

sargassum fish, a predator with algae-like appendages who hovers motionless among the

Sargassum. Fossils of similar fishes have been found in fossil bays of the former Tethys Ocean, in what is now the

Carpathian

region, that were similar to the Sargasso Sea. It is possible that the

population in the Sargasso Sea migrated to the Atlantic as the Tethys

closed at the end of the Miocene around 17 Ma.

[38]

The origin of the Sargasso fauna and flora remained enigmatic for

centuries. The fossils found in the Carpathians in the mid-20th century,

often called the "quasi-Sargasso assemblage", finally showed that this

assemblage originated in the

Carpathian Basin from were it migrated over

Sicily to the Central Atlantic where it evolved into modern species of the Sargasso Sea.

[39]

The location of the spawning ground for European eels

remained unknown for decades. In the early 19th century it was discovered that the southern Sargasso Sea is the spawning ground for both the

European and

American eel

and that the former migrate more than 5,000 km (3,100 mi) and the

latter 2,000 km (1,200 mi). Ocean currents such as the Gulf Stream

transport eel larvae from the Sargasso Sea to foraging areas in North

America, Europe, and Northern Africa.

[40]

No comments:

Post a Comment